Mysteries

Big open puzzles that haven't been resolved yet.

Project maintained by ege-erdil Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

The Industrial Revolution

What is perhaps most mysterious about the Industrial Revolution is the lack of recognition among most people that there is a big mystery to be explained here. Wikipedia states that

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Europe and the United States, in the period from between 1760 to 1820 and 1840. This transition included going from hand production methods to machines, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, the increasing use of steam power and water power, the development of machine tools and the rise of the mechanized factory system. The Industrial Revolution also led to an unprecedented rise in the rate of population growth.

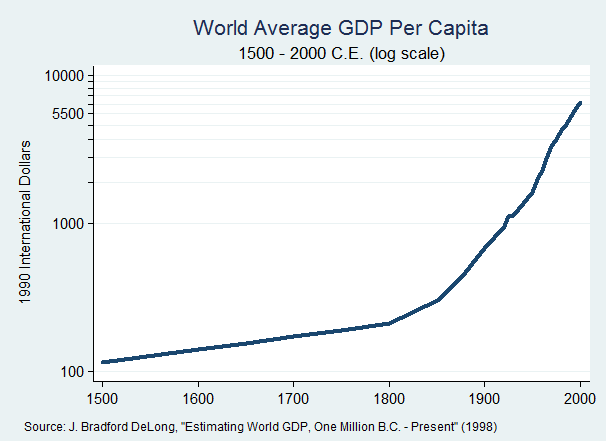

This is not even an adequate definition of the Industrial Revolution. As Robin Hanson notes in Long-Term Growth As A Sequence of Exponential Modes, what we really have to explain is a phase transition in economic activity. Sometime around the year 1800, GWP (gross world product) went from doubling roughly every 1000 years to doubling roughly every 15 years, and we have been in the new regime ever since then. This is a dramatic transformation of the world economy, comparable to a phase transition from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas, and merits an explanation that is comparable to Landau’s model of second order phase transitions.

Just in case this description is not sufficiently evocative, here is a picture of what that looks like:

The transition was not even that smooth, and there’s a visible elbow point on the graph around the year 1800. This is the mystery that has to be explained - so what explanations have people offered for this remarkable phenomenon? It’s of course impossible for this list to be exhaustive, but I try to cover some of the common explanations along with the reasons why they fall short here.

There’s nothing to explain

This view denies the existence of the mystery to begin with. As one Reddit user expresses it,

The Industrial Revolution wasn’t all one thing any more than World War II was all one thing. It happened in fits and starts around the world. It was expressed differently on a local basis.

To the contrary, the remarkable thing about economic growth in the industrial era is its stability. Variations in growth rates in the industrial era are much smaller than the variation between the industrial era and what came before, and for the most part countries which are able to grow more quickly can do so because they are catching up to countries on the frontier.

It is true that the industrial phase transition happened in different places at different times, but that doesn’t mean “it’s not all one thing”, any more than the fact that water freezes at different temperatures at different locations is evidence that the liquid to solid phase transition is “not all one thing”.

I think anyone who can look at the graph above and conclude that “there’s nothing to explain here” needs to visit an ophthalmologist.

It’s exponential growth

This view maintains that the Industrial Revolution happened because of the tendency towards expoential growth built into technological progress and capital accumulation. The more we accumulate capital goods or discover new technologies, the more productive we become and the more easily we can build new machines or conduct research in novel directions.

This explanation falls flat because what we’re trying to explain is not the phenomenon of exponential growth itself, but the phase transition from one growth rate to another growth rate: roughly from a growth rate of 0.1% per year to a growth rate of 4.5% per year. If this explanation were true, then we would have simply continued to grow at our old growth rate of 0.1% per year, and there would have been no industrial revolution to begin with.

It’s the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, etc.

There are numerous problems with this explanation. The first one is that the timing doesn’t fit at all. The Enlightenment was already over when the first signs of the Industrial Revolution started to appear. Wikipedia says that

Some date the beginning of the Enlightenment to René Descartes’ 1637 philosophy of Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”), while others cite the publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687) as the culmination of the Scientific Revolution and the beginning of the Enlightenment. French historians traditionally date its beginning with the death of Louis XIV of France in 1715 until the 1789 outbreak of the French Revolution. Most end it with the beginning of the 19th century.

Here is a table of French real GDP per capita in 2011 dollars according to the 2020 release of the Maddison Project:

| Year | French GDP per capita |

|---|---|

| 1637 | 1659 |

| 1687 | 1710 |

| 1715 | 1659 |

| 1789 | 1779 |

| 1820 | 1809 |

| 1850 | 2546 |

| 1880 | 3379 |

From this table it’s rather obvious that France only transitioned to the industrial era after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. If the Industrial Revolution was indeed a product of the Enlightenment, then what we would have to believe is that the Enlightenment had absolutely no effect on economic activity for the hundred or so years that it was actually happening, and only a few decades after it was over did we finally begin to see its effects. However, when we allow ourselves to have such enormous latitude in fitting an explanation to the data, we could just as well claim that the Industrial Revolution was a delayed consequence of the dramatic rise in wages caused by the Black Death in Europe.

Without at least a precise correspondence between the timelines, the mere fact that these two things happened at “around the same time”, give or take a hundred years, is not even strong evidence that they are correlated, much less that there is a causal relationship between them.

The picture looks a little better with the United Kingdom:

| Year | UK GDP per capita |

|---|---|

| 1637 | 1476 |

| 1687 | 2169 |

| 1715 | 2294 |

| 1789 | 2888 |

| 1820 | 3306 |

| 1850 | 4332 |

| 1880 | 5997 |

In the “Enlightenment Era” from 1637 to 1789, Britain was likely the fastest growing economy in the world: population grew by about 50% and GDP per capita doubled, meaning that British GDP likely tripled over the course of 152 years. That’s a mean growth rate of around 0.7% per year, which is incidentally approximately the geometric mean of the farming era growth rate of 0.1% per year and the industrial era growth rate of 4.5% per year.

I think a plausible explanation for this is that Britain was the first country in the world to experience the industrial phase transition, and for them the transition was considerably smoother than it was for the rest of the world. However, it’s still a fact that even for the UK the transition was only over well after the Enlightenment had ended, which makes this particular explanation look quite weak.

It’s a demographic transition

This explanation was proposed by Robert Lucas in Industrial Revolution: Past and Future. Quoting Lucas:

One of these successful theories is the product of Smith, Ricardo, Malthus and the other classical economists… Their theory is consistent with the following stylized view of economic history up to around 1800. Labor and resources combine to produce goods—largely food, in poor societies—that sustain life and reproduction. Over time, providence and human ingenuity make it possible for given amounts of labor and resources to produce more goods than they could before. The resulting increases in production per person stimulate fertility and increases in population, up to the point where the original standard of living is restored… The model predicts that the living standards of working people are maintained at a roughly constant, “subsistence” level…

The modern theory of sustained income growth, stemming from the work of Robert Solow in the 1950s, was designed to fit the behavior of the economies that had passed through the demographic transition. This theory deals with the problem posed by Malthusian fertility by simply ignoring the economics of the problem and assuming a fixed rate of population growth. In such a context, the accumulation of physical capital is not, in itself, sufficient to account for sustained income growth. With a fixed rate of labor force growth, the law of diminishing returns puts a limit on the income increase that capital accumulation can generate. To account for sustained growth, the modern theory needs to postulate continuous improvements in technology or in knowledge or in human capital (I think these are all just different terms for the same thing) as an “engine of growth.” Since such a postulate is consistent with the evidence we have from the modern (and the ancient) world, this does not seem to be a liability of the theory.

The mechanism is then that there is some kind of phase transition that takes place in population dynamics from the pre-industrial era to the industrial era. While productivity growth existed in both periods, the gains in the pre-industrial era were only reflected in population growth as wages fell back to subsistence levels in a Malthusian fashion - the population dynamics were such that people simply kept having more children until the marginal product of labor fell back to where it had been before. In contrast, this Malthusian dynamic seems to be inoperational in industrial societies, and therefore the productivity gains are translated into an increase in the living standards of the mass of the people.

This explanation can’t possibly account for the Industrial Revolution, because the Industrial Revolution is not just an increase in per capita growth rates, it’s an increase in overall growth rates. If this explanation were correct, while it’s true that we would see faster per capita income growth in the industrial era, we would see slower overall income growth, because we would be losing the gain in production that would result from an increase in the labor force. While such an increase lowers wages due to the diminishing marginal product of labor, it doesn’t lower overall production, so this explanation is totally inadequate for explaining the nearly 50-fold increase in overall growth rates that took place in the industrial phase transition. The best example of this is perhaps the Black Death, which led to a large increase in the wages of European workers due to the dramatic fall in population caused by the disease (according to Maddison, French GDP per capita was higher in 1370 than it was in 1820), with no corresponding increase in long-run growth rates.

It is, however, correct that the Industrial Revolution is accompanied almost everywhere by falling fertility rates. The mistake in this argument is to invert the direction of causality: in fact industrial revolution is what causes a fall in fertility rates, not the other way around.