Mysteries

Big open puzzles that haven't been resolved yet.

Project maintained by ege-erdil Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

This page contains a non-exhaustive list of big open problems that remain unsolved despite being both highly puzzling and of great significance. They have resisted attempts by countless people to explain them - perhaps you will succeed where they have failed?

The list will be in descending order of importance that I assign to the puzzles. First, a list of the mysteries currently on the page:

- The Industrial Revolution, page link

- Why do wars happen?, page link

- Puzzle of excess volatility, page link

- Nominal shocks have real effects?, page link

The Industrial Revolution

What is perhaps most mysterious about the Industrial Revolution is the lack of recognition among most people that there is a big mystery to be explained here. Wikipedia states that

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Europe and the United States, in the period from between 1760 to 1820 and 1840. This transition included going from hand production methods to machines, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, the increasing use of steam power and water power, the development of machine tools and the rise of the mechanized factory system. The Industrial Revolution also led to an unprecedented rise in the rate of population growth.

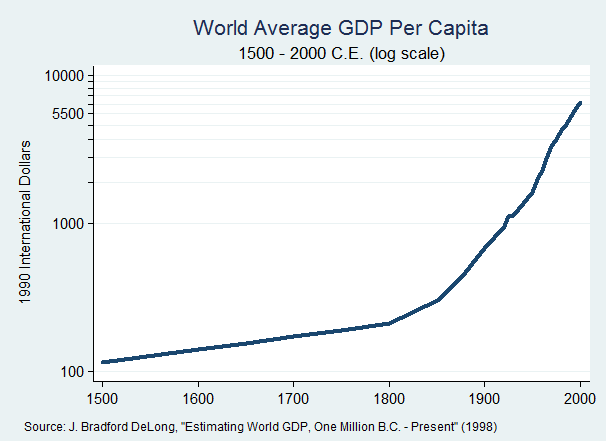

This is not even an adequate definition of the Industrial Revolution. As Robin Hanson notes in Long-Term Growth As A Sequence of Exponential Modes, what we really have to explain is a phase transition in economic activity. Sometime around the year 1800, GWP (gross world product) went from doubling roughly every 1000 years to doubling roughly every 15 years, and we have been in the new regime ever since then. This is a dramatic transformation of the world economy, comparable to a phase transition from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas, and merits an explanation that is comparable to Landau’s model of second order phase transitions.

Just in case this description is not sufficiently evocative, here is a picture of what that looks like:

The transition was not even that smooth, and there’s a visible elbow point on the graph around the year 1800. This is the mystery that has to be explained - so what explanations have people offered for this remarkable phenomenon? It’s of course impossible for this list to be exhaustive, but I try to cover some of the common explanations along with the reasons why they fall short here.

Why do wars happen?

Warfare is a puzzling human activity all around, and there are several unresolved questions about it which are mystifying.

The first one is why wars happen at all. A good introduction to this puzzle is Rationalist explanations for war by James D. Fearon. As Fearon summarizes,

The central puzzle about war, and also the main reason we study it, is that wars are costly but nonetheless wars recur. Scholars have attempted to resolve the puzzle with three types of argument. First, one can argue that people (and state leaders in particular) are sometimes or always irrational. They are subject to biases and pathologies that lead them to neglect the costs of war or to misunderstand how their actions will produce it. Second, one can argue that the leaders who order war enjoy its benefits but do not pay the costs, which are suffered by soldiers and citizens. Third, one can argue that even rational leaders who consider the risks and costs of war may end up fighting nonetheless.

While it appears intuitively “obvious” to most people why there should be wars in a world of scarcity and conflicting aims, this obvious fact is in fact not as obvious as it might first appear. Fearon proposes a simple model of a dispute, in which two agents disagree about where the value of some variable \( x \) restricted to the closed interval \( [0, 1] \) should fall: the first agent has a payoff \( u(1-x) \) while the second agent has a payoff \( v(x) \), where \( u \) and \( v \) are two increasing utility functions. They can either choose to compromise at some value of x in between, or they can choose to go to war, in which case the first agent wins with a probability \( p \) and the second agent wins with a probability \( 1-p \). The side that wins gets to achieve the optimal outcome for themselves, however there is a fixed cost \( c \) of going to war which is wasted.

If the two sides go to war, then the first agent has an expected payoff \( p u(1-c) + (1-p) u(0) \), while the second agent has an expected payoff \( p v(0) + (1-p) v(1-c) \). Now, if we assume \( u \) and \( v \) are concave (not necessarily strictly) and strictly increasing, it’s clear that both sides are better off compromising at the value \( x = 1-p \) than going to war.

This toy model is interesting because it is a proof that one of its features must be violated if war is ever to be a rational choice. Fearon explores several possibilities: perhaps the issues over which wars are fought are indivisible so that no compromises are possible, perhaps agents don’t have preferences that can be represented by concave utility functions so that their willingness to take risk overwhelms the costs of war, and perhaps the two sides disagree about their own chance of winning a war. These attempts to resolve the puzzle have their own problems, however.

An alternative account which is popular among people familiar with the hawk-dove game is that many real world interactions between governments are essentially like a hawk-dove game in which the two sides are indistinguishable, so the only Nash equilibrium is one in which people play a mixed strategy between hawk and dove, resulting in occasional wars with some arrival rate when two players play hawk simultaneously. The obvious problem with this argument is that the two sides are in fact distinguishable in the real world, and under those conditions the hawk-dove game does not have a mixed Nash equilibrium: the two equilibria are the ones in which one player plays hawk and the other player plays dove, resulting in no wars being observed in equilibrium.

More commentary on this puzzle and attempts to answer other criticisms may be found here.

Puzzle of excess volatility

The puzzle of excess volatility is the apparent paradox that broad market stock indices such as the S&P 500 are much more volatile than would be justified by the volatility of the underlying discounted dividend flows. It extends to other asset classes as well, such as foreign exchange and corporate bonds, but for now I’ll focus only on the stock indices.

Naively, we might expect that given a stock which pays a certain cash flow (including both dividends and buybacks) to the investors, the price of the stock would be the present value of these cash flows discounted at some rate of return. If this were the case, volatility in stock indices would only be driven by volatility of expectations about future dividend flows. However, under this picture it’s difficult to justify the observed volatility of stock indices, which is 15% annualized in good times and can go up to 80% annualized as we have seen in March 2020. This is because while there can be substantial uncertainty about current dividends, what dividends will be this quarter or this year should not have much effect on the stock price under a discount rate formalism.

A little financial-econometric history by John H. Cochrane summarizes the history of the puzzle and confirms the above reasoning. I highly suggest you read it, since it contains a lot of equations that I am unable to display here due to GitHub Markdown’s lack of support for LaTeX. The upshot is that the data suggests all of the variation in dividend yields of broad market stock indices corresponds only to variation in future returns, with none of it corresponding to variation in future dividends. In other words, if prices are high today relative to dividends today, that doesn’t mean dividends will grow faster in the future or that prices will grow faster in the future - it only means that you’ll get, on average, a worse return that you would’ve otherwise got. The reason the naive argument fails is that it assumes rates of return don’t vary over time, while variation in returns is the primary driver of the phenomenon of excess volatility.

Of course, from one perspective this does nothing to resolve the puzzle because we can always, after appropriate log-linearization of the definition of returns, express the current price-dividend ratio in terms of future dividend growth, future returns and future price-dividend ratios. A true resolution of the puzzle would also include an explanation of why returns on the stock market vary by such huge amounts, and it’s the explanation for this fact which has proved elusive. Read more about this puzzle, and attempts to resolve it, here.

Nominal shocks have real effects?

This is a mystery that is at the heart of macroeconomics, and one that has still not been resolved satisfactorily. If you’ve ever heard about aggregate supply curves or Phillips curves, you likely already know what this puzzle is about, but if not here is a short explanation:

In principle, thinking of money as a unit of account, we might expect that changes in the value of money should not have much real impact on the economy. While how fast or how slowly money loses its value should affect how much of it people choose to hold through an “inflation tax”, there should be no particular reason that a one-time change in the value of a currency should have any impact on economic activity, since the prices of goods and services would just adjust accordingly so that the same fraction of the total money stock still has the same purchasing power as before the revaluation.

Indeed, sometimes this seems to be the case. When Italy knocked off three zeroes from the Italian lira in 1986, the change in the unit of account had no effect on Italian economic life. Prices and wages merely fell by a factor of 1000 and life continued as before. There are many other examples of such currency revaluations, none of them having any noticeable effect on anything beyond the number of zeroes in the bills people carry in their wallets.

However, this flies in the face of the common belief that monetary policy is powerful and has a lot of impact on economic life. If all the impact monetary policy had on the economy is the inflation tax borne by people who hold non-interest bearing currency, the impact would be miniscule compared to any other tax on the books. The way macroeconomists have historically gotten around this problem is the postulate of nominal rigidities: the idea that since the currency used in a particular economy serves as the unit of account, a lot of quantities in an economy are indexed to the value of the currency (in other words, they are nominal) without any correction for inflation or deflation, and on top of that they are also typically slow to adjust in response to changes in the value of the currency. As Ball and Mankiw state in A Sticky Price Manifesto:

We believe that sticky prices provide the most natural explanation of monetary non-neutrality since so many prices are in fact, sticky… based on microeconomic evidence, we believe that sluggish price adjustment is the best explanation for monetary nonneutrality.

This phenomenon, if real, allows monetary policy shocks to have a much more significant impact. For example, a big unexpected increase in inflation now obviously creates problems for financial institutions who hold onto long-term debts while leveraging through short-term borrowing; and a big deflation can cause an economic depression since nominal wages might be slow to adjust, causing real wages to be too high for a period in which the only recourse for employers is to fire workers since they can’t afford to pay them the new, higher real wage.

The fact that non-inflation indexed debt contracts, wage contracts, et cetera are common even in countries with relatively high inflation rates is not under dispute, though as Stephen Williamson points out in New Monetarist Economics: Models, there is some dispute about the extent to which price or wage stickiness beyond what is present in these contracts is a real phenomenon. The mystery here is why people wouldn’t arrange debt and employment contracts, product orders and so on in such a way that they are naturally indexed against inflation, and why it would take them a long time to adjust when there is a change in the value of the currency. The Italian experiment cited above shows that economies are certainly easily capable of doing such a thing, so why don’t they if these frictions impose such large costs? Or is the truth that the frictions don’t impose large costs, and the nominal rigidity-based macroeconomic paradigm is simply mistaken?

I go into more detail about this puzzle and criticize some of the attempts to resolve it here.

Bonus mysteries

The mysteries in this section might already have satisfactory resolutions, but nevertheless they are mysteries to me. Don’t expect long expositions or separate pages on these mysteries.

The baby boom

What caused the increase in total fertility rates in many Western countries following the Second World War? Was it the war itself, or did people have the kids they had been postponing until then due to the Great Depression, or was there some other reason? Was it the so-called postwar economic boom that was responsible?

For such a remarkable demographic phenomenon, there is surprisingly little understanding of the causes of the baby boom and why it ended. Until then, total fertility rates had been in a downward trend throughout the Western world, and after this brief interruption in the postwar period the trend resumed until where we are today.